Description

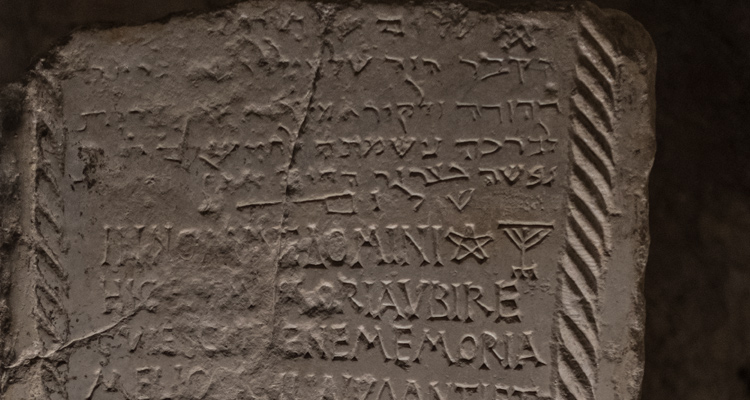

The famous trilingual headstone, featuring parallel translations in Greek, Latin and Hebrew, dates from the 6th century and belongs to the grave of Meliosa, a young Jewish woman. It bears testimony to the Jewish community’s settlement in Tortosa. This epigraphic element provides proof that the Jews were present in the city even during ancient times. After the city was conquered by Ramon Berenguer IV in 1148, the count donated the old Arab shipyards to the Jewish community for the construction of 60 houses. And so, the old Jewish quarter was born. This is the earliest evidence of a quarter or neighbourhood inhabited exclusively by Jews in Tortosa. Later, at the beginning of the 13th century, a new Jewish quarter was built. This Jewish quarter has remained almost intact, and even now, the structure of the streets and some of the place names are the same. Tortosa’s Jewish quarter provides for a short but fascinating tour that draws us into its narrow white streets and takes us on a trip to the past.

The Synagogue. The first stop on our tour of Tortosa’s Jewish quarter is the site of the old synagogue. There are information panels and small maps throughout the Jewish quarter to help visitors find their bearings and locate the next landmark. The existence of a synagogue has been documented since the beginning of the 14th century. The synagogue, or temple of the Jews, was a place dedicated to prayer and religious ceremonies. In addition to the synagogues, there were also baths where purification rituals were carried out. Next, if we continue along Carrer de Jerusalem, we shall come to the Jewish butcher shop.

The Jewish butcher shop. On this same corner, but on Carrer d’en Fortó, stands the Jewish butcher shop. Belonging to the Christian Sentmenat family and subleased by the Jews, the butcher shop was managed by the aljama or community government, which provided the means required to ensure that the meat was purified, or kosher.

The Jewish quarter oven. The oven, known as the Forn del Senyor Rei, still stood at the end of Carrer d’en Fortó in the 17th century. The aljama had institutions and establishments to provide basic functions, and one of these was the Jewish quarter oven, where Jews baked unleavened bread. The oven was an important source of income for the city. The Montcada family and the Order of the Temple benefited from charging rent for baking bread in the Jewish quarter oven in the Middle Ages.

The pottery. If we turn towards Carrer Major de Remolins, we come to the site where the pottery stood. The Islamic pottery tradition can be traced back to the Late Middle Ages and was carried out in the neighbourhood of Remolins from the late 19th century to the first half of the 20th century. Dedicated to the production of ceramic containers for domestic and agricultural use, the building was also used for housing. The ground floor courtyard still conserves the circular oven that was used to bake the clay. If we continue along the same street, we shall come to the building known as the Synagogue, or the Casa de Sant Jordi.

Synagogue or Casa de Sant Jordi. This building, popularly known as the Synagogue, is medieval in origin. It was built in the 14th century as a hospital. In the 18th century, the property was converted into cavalry barracks and became known as the Quarter del Príncep or the Quarter de Remolins. Here we can see the foundations of the 14th-century walls.

The foundations of the 14th-century walls. The urban restructuring project that involved construction of the expansion district during the 19th century led to the demolition of the section of the wall that ran from the Célio or Grossa de Vimpeçol Tower to the Vimpeçol de Ribarech or Rodona Tower, which stood on the banks of the river. From this stretch of wall, it is still possible to follow the trail that runs parallel to Barranc del Cèlio. The Vimpeçol gate, which was located at the top of Carrer Major de Remolins, was one of the main entrances to the city, as it linked the towns on the left bank of the river and was the exit to the Royal Road to Zaragoza.

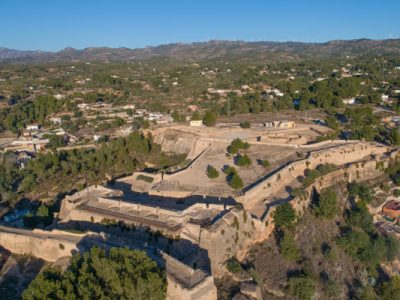

Célio Tower. This area of fortification extends along the north side of the city’s walled enclosure, where the neighbourhood of Remolins is located. Its layout and a large section of the parapet walk have been preserved intact. Most of it corresponds to a stretch of wall, except for the fortified towers at both ends, at the bottom of the cliff. These are the so-called Célio or Grossa Tower and, in the highest part, the remains of two square towers that have been incorporated into the structure of the fortified complex known as the Sant Joan outposts, to which they are attached. It is a short walk from the walls to the charming Jews’ gate.

The Jews’ gate. Standing right in the middle of the 14th-century medieval wall that led to the Jewish quarter is the Jews’ gate, which provided access to the Jewish burial ground and the gardens located outside the walls of the city. The gate was used as an alternative exit from the walled area whenever the Ebro river flooded. Once we have seen the Jews’ gate, we shall go back a short distance and head onto Carrer de la Vilanova.

Carrer de la Vilanova. The labyrinthine structure of the Jewish quarter is interrupted by this street, whose linear layout and width make it unique. It was constructed at the beginning of the 15th century, when houses and hostels were torn down to give the street its current appearance and structure.

Finally, our tour of Tortosa’s Jewish quarter concludes in the beautiful Plaça de la Figuereta, which retains an ancient well that stands in the centre of a space filled with pure tranquillity.